Bootlegging as Material Culture

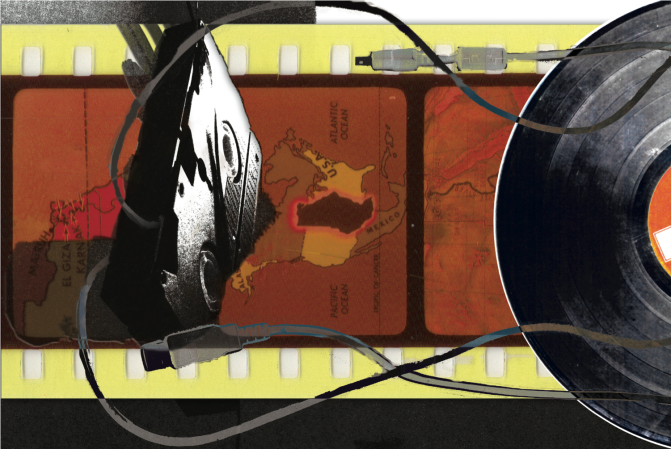

Image by Joshua Wright

Long before “cassette culture” and DIY, there was a distinct culture of homemade media: bootleg records. Even with the technological limitations of shellac and vinyl, pirates, collectors, and music fans figured out how to reproduce sound. In doing so, they also invented a unique aesthetic of piracy in the form of the sleeves and liner notes of illicit (or at least unauthorized) records. Due to a loophole in copyright that left sound recordings unprotected in the United States until 1971, bootleggers could at least claim that they operated in a realm of quasi-legality (though that claim was often disputed, as I explore in my book Democracy of Sound). Legal hijinks notwithstanding, bootleg records still had a touch of mischief about them: one of the most infamous (or celebrated, depending on your point of view) of bootleggers was jazz fan Dante Bollettino, who pressed his records under the “Jolly Roger” label.

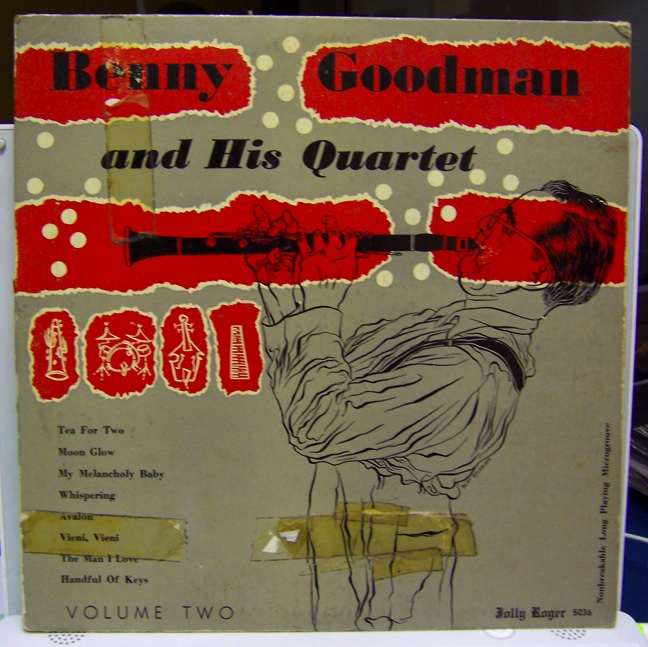

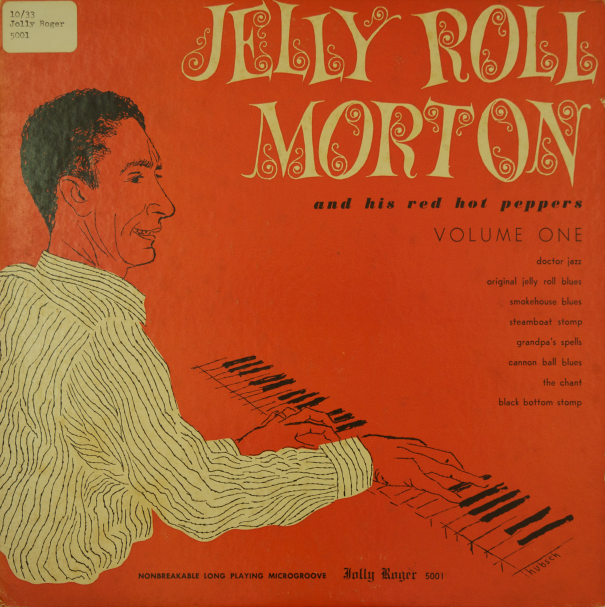

Notably, most of Bollettino’s Jolly Roger records had no liner notes on the back and displayed no address–a hallmark of bootleg style that is not surprising. The Roger bootlegs, though, still possessed the spare and iconic flare that defined numerous releases by Benny Goodman, Jelly Roll Morton, Cripple Clarence Lofton and others.

Other pirates infused their packaging and cover designs with a wry sense of humor, and few were so clever as the famous New York bootlegger Boris Rose, who manufactured countless jazz, blues, classical and showtunes records out of his small Manhattan apartment on 1st Avenue. Many of Rose’s records were captured from fleeting radio broadcasts and remain invaluable documents of an era of ephemeral media that is largely lost to scholars. And nearly every record was published by a different fictional label (like Jung Cat Records below), while Rose authored liner notes under phony names like Astyanax Schwarz and Kentwood P. Axtor. Rose even inscribed humor into the tiniest fine print: a message along the edge promises that the disc is “a good musical record from Duck Run, Ohio”–a village made famous years later as the hometown of Ohio Gov. Ted Strickland, and even then it was best-known for being extremely tiny and obscure.

By the late 1960s, bootleggers took advantage of the new technology of magnetic tape to get hold of unreleased music that leaked from the studio, as well as to surreptitiously record live performances of artists such as Neil Young and Jimi Hendrix. The most famous such bootleg was Bob Dylan’s Great White Wonder, the “basement tapes” that the folksinger recorded with the Band in 1967 but opted not to release. When the recordings leaked in 1969, they touched off a flurry of piracy, as bootleggers embraced a flamboyant rhetoric that mashed together New Left radicalism and countercultural liberation.

The original Great White Wonder bootleg featured a plain white cover, seemingly modeled after the Beatles’ “White album” of the year before, but other iterations of the basement tapes soon became more complex and creative.

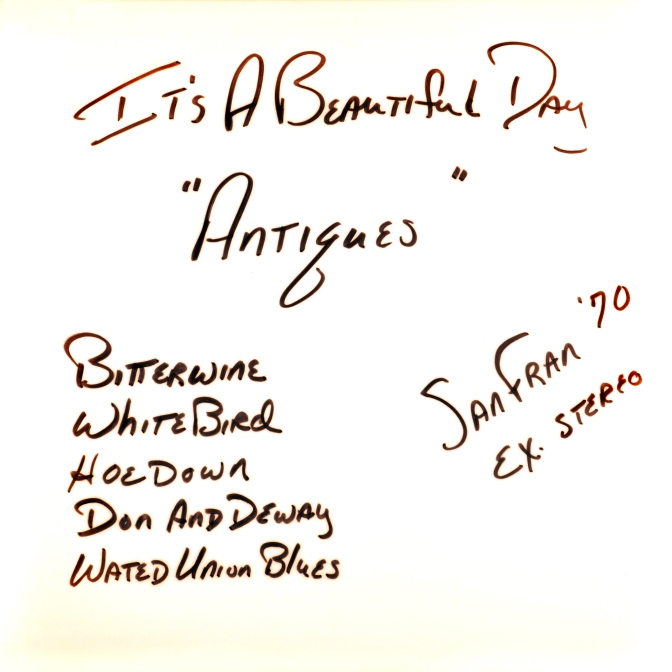

Some, though, remained modest and unadorned, like this recording of the San Francisco jam band It’s a Beautiful Day, which resembles nothing so much as a CD-R, hastily labeled with a permanent marker.

Many live bootlegs by the notorious California pirate Rubber Dubber featured the simple black-and-white aesthetic of Neil Young’s I’m Happy Y’all Came Down, though sleeves increasingly featured more abstract and elaborate imagery, such as this bootleg of Elton John and Leon Russell.

Bootlegs also provided an outlet in which pirates (and fans, for many bootleggers were fans and collectors themselves, rather than pure profiteers) could satirize and otherwise tweak the image of the artists whose music they recorded and copied. The sleeve for Bob Dylan’s Little White Wonder, for instance, had some fun at the expense of the erstwhile Robert Zimmerman, and bootlegs of the Rolling Stones and Elvis Presley frequently depicted them in ways that, at the very least, were not the way they chose to represent themselves.

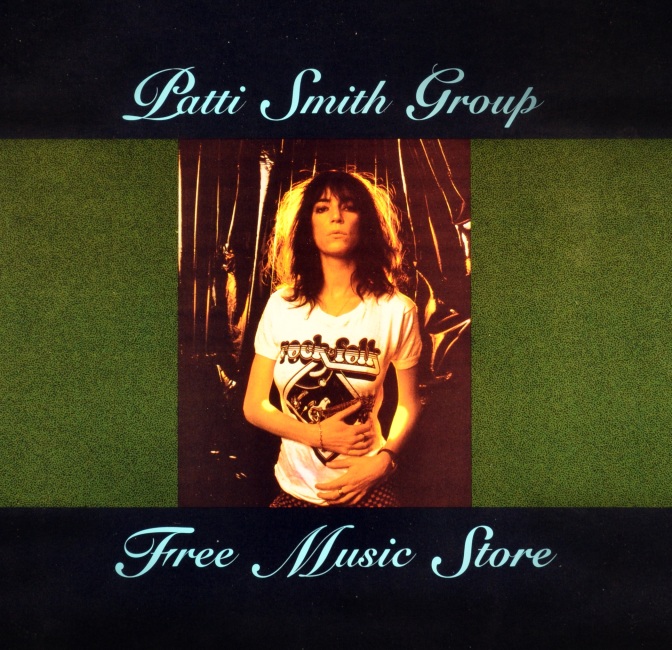

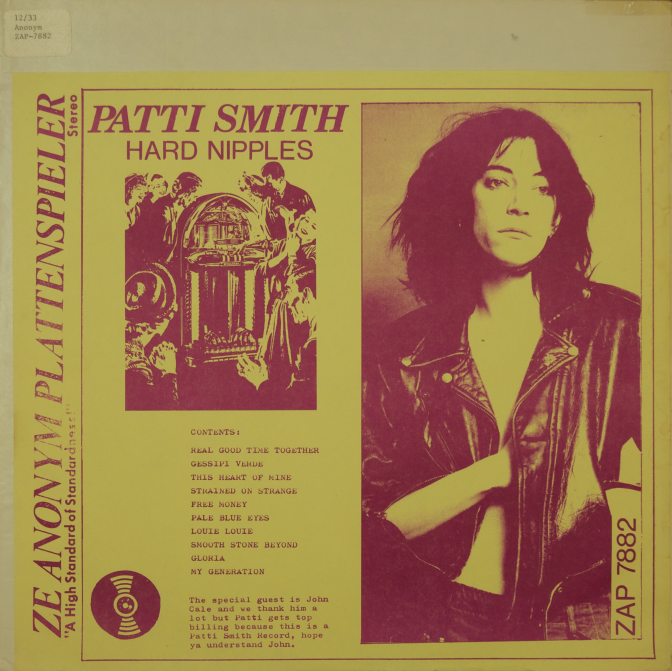

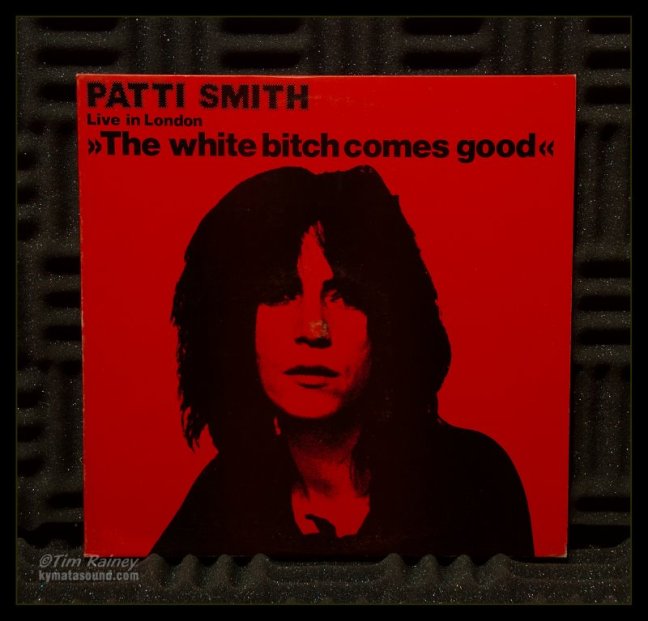

And while bootlegs created a space for critique–quite literally, since the surface of a vinyl LP sleeve offers a bigger canvas than the bootleg cassette ever could–the politics of representation could still be dicey. Punk pioneer Patti Smith is said to have embraced bootlegging and, in concert, even attributed some of her songs to have come from the seminal bootleg Teenage Perversity and Ships in the Night, rather than their official releases. The Smith disc below toys with its own status as a pirate record with the seemingly paradoxical idea of a “free music store.” But as other records showed, pirates’ depiction of Smith could go from punk and edgy to possibly sexist.

Whether their content was Patti Smith or Prince, bootleg records offer historians and music lovers not just a document of long-gone radio broadcasts, concerts, and unreleased records, but a little-known example of a mid-twentieth century folk culture: DIY media in an era before cassettes, four-track recording and iMovie democratized access to media production on a more massive scale. Paradoxically, perhaps, the medium of vinyl provided an arena for sharing and commenting on music, while stamping the work of pop and punk icons with the listener-pirate’s own unique aesthetic and agenda.

Some records sit in university libraries and archives, largely unnoticed, while others can be found circulating on eBay and other online markets. They are a prologue, perhaps, to the sharing culture that took shape in a post-punk era of the late twentieth century (or a post-Napster era of the early twenty-first century, if you prefer), but they provide a fascinating window into the ways that fans, collectors, and, yes, outright entrepreneurs threaded their way through a media economy seemingly geared toward standardized, mass production. As scholars such as James Hildebrand and Brian Larkin have begun to recognize, they represent an archive of primary sources and material culture that deserve a history of their own, and have a lot to tell us about the life of music in the mid-twentieth century.

This piece is cross-posted from Tropics of Meta with permission from the author.

Comments are Closed